|

| |||

| The original Russian word Bakhtin used for Heteroglossia was разноречие (raz-no-rech-i-ye), derived from "разно," or "different" and "речи," meaning "speech." | ||||

| ||||

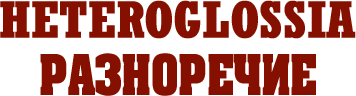

This is a broader concept than polyphony. It is a complex mixture of languages and world views that is always...dialogized, as each language is viewed from the perspective of the others. This is a broader concept than polyphony. It is a complex mixture of languages and world views that is always...dialogized, as each language is viewed from the perspective of the others.

(Dimitriadis & Kamberelis, 2006, p.51) |

||||

|

|

| |||

|

For Bakhtin, discourse always articulates a particular view of the world... 'Heteroglossia' refers to the conflict

between 'centripetal' and 'centrifugal', 'official' and 'unofficial' discourses

within the same national language. 'Heteroglossia' is also present, however, at the (q.v.) micro-linguistic scale; every utterance contains within it the

trace of other utterances, both in the past and in the future.

(Roberts, 1994, p. 248) | ||||

| ||||

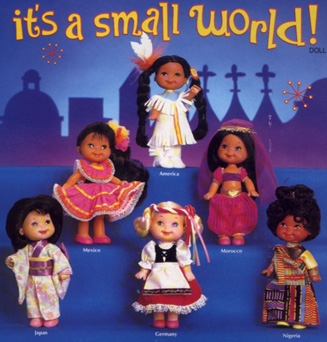

| What are these "centripetal" and "centrifugal" forces? How do they work? | ||||

|

|

| |||

|

Thus a unitary language gives expression to forces

working toward concrete

verbal and ideological unification and centralization, which

develop in vital connection with the processes of sociopolitical

and cultural centralization. ...The victory of one reigning language (dialect) over the others, the supplanting of languages, their enslavement, the process of illuminating them with the True Word, the incorporation of barbarians and lower social strata into a unitary language of culture and truth, the canonization of ideological systems, philology with its methods of studying and teaching dead languages, languages that were by that very fact "unities," Indo-European linguistics with its focus of attention, directed away from language plurality to a single proto-language-all this determined the content and power of the category of "unitary language" in linguistic and stylistic thought, and determined its creative, style-shaping role in the majority of the poetic genres that coalesced in the channel formed by those same centripetal forces of verbal-ideological life. But the centripetal forces of the life of language, embodied in a "unitary language," operate in the midst of heteroglossia. At any given moment of its evolution, language is stratified not only into linguistic dialects in the strict sense of the word...but also...into languages that are socio-ideological: languages of social groups, "professional" and "generic" languages, languages of generations and so forth. From this point of view, literary language itself is only one of these heteroglot languages - and in its turn is also stratified into languages. (Bakhtin, 1975/1981, p. 271) |

||||

| ||||

So, no matter how hard a totalizing, centrifying, centripedal force tries to absorb and incorporate difference into its singular vision...

That synthesizing voice will still be just one voice among countless other institutional, popular, academic, vulgar, formal, and informal voices.

|

||||

|

|

| |||

| According to Bakhtin (1986), the very essence of speech

as a semiotic activity is multivoiced, filled with underlying

principles, with unique points of view and forms of conceptualizing

the world, characterized by various meanings

and values. Therefore, language is by its very nature heteroglot,

representing at any given moment “the co-existence

of socio-ideological contradictions between the present and

the past, between differing epochs of the past, between

different socio-ideological groups in the present, between

tendencies schools, circles, and so forth, all given a bodily

form” (1986, 291). (Cuenca, 2010, p.46) |

||||

Ayers, W., & Alexander-Tanner, R. (2010). To teach: The journey, in comics. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Discourse in the novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by Mikhail Bakhtin (pp. 259-422). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1975).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Epic and Novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by Mikhail Bakhtin (pp. 3-40). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1941).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Forms of time and of the chronotope in the novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by Mikhail Bakhtin (pp. 84-258). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1937).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). From Rabelais and his world (H. lswolsky, Trans.). In P. Morris (Ed.), The Bakhtin reader (pp. 195-244). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1965).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Problems of dostoevsky's poetics. (C. Emerson, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published in 1963).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). From speech genres and other late essays (H. lswolsky, Trans.). In P. Morris (Ed.), The Bakhtin reader (pp. 81-87). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1976).

Cuenca, A. (2010). Democratic means for democratic ends: The possibilities of Bakhtin's dialogic pedagogy for social studies. The Social Studies, 102(1), 42-48.

Dimitriadis, G., & Kamberelis, G. (2006). Theory for education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Miles, A. P. (2010). Dialogic encounters as art education. Studies in art education: A journal of issues and research 51(4), 375-379.

Roberts, G. (1994). A glossary of key terms. In P. Morris (Ed.), The Bakhtin reader (pp. 245-252). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rule, P. (2011). Bakhtin and Freire: Dialogue, dialectic and boundary learning. Educational philosophy and theory 43(9), 924-942.