This module introduces a variety of concepts and artists related to Indigenous survivance and futurity. We will encounter artists who imagine futures that do not assume or center the presence of settlers on colonized lands, and that celebrate the ongoing contemporary existence of Indigenous people, which prevents settler-exclusive visions of the future from coming to pass.

Unangax̂ scholar-educator Eve Tuck (enrolled member of the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, Alaska) and settler scholar-educators Marcia McKenzie and Mary McCoy described Indigenous futurity this way:

Replacement [settler replacement of Indigenous peoples] relies on fantasies of the extinct or becoming-extinct Indian as natural, forgone, inevitable, indeed, and evolutionary (see Tuck and Gaztambide-Fernández 2013). Replacement is invested in settler futurity; in our use, futurity is more than the future, it is how human narratives and perceptions of the past, future, and present inform current practices and framings in a way that (over)determines what registers as the (possible) future. (Tuck, McKenzie, & McCoy, 2014, p. 17, emphasis added)

Scholar Gerald Vizenor (enrolled member, Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) described survivance this way:

Native survivance is an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion; survivance is the continuance of stories, not a mere reaction… Survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, detractions, obtrusions, the unbearable sentiments of tragedy, and the legacy of victimry. (Vizenor, 2008, p. 1, emphasis added)

Reading and Learning

Read all three of the three readings below to explore. Each provides a different lens on how digital technologies (for artmaking and for other purposes) participate in Indigenous Futurity.

Daniel Taipua (Waikato-Tainui Māori) writes about the science fictional video game Umurangi Generation by artist Naphtali Faulkner (Ngai Te Rangi Māori), and discusses how “[e]very single artistic vision of a Māori future or a future for Māori is an act of resistance against extinction.”

Michael Running Wolf (citizen, Northern Cheyenne) writes a science-fictional vignette of visitors’ experience of an AI system that manages cultural preservation in a decolonized Hawai’i, and then draws upon his Computer Science background to talk about the practical ways Indigenous communities may leverage AI technologies in cultural preservation work.

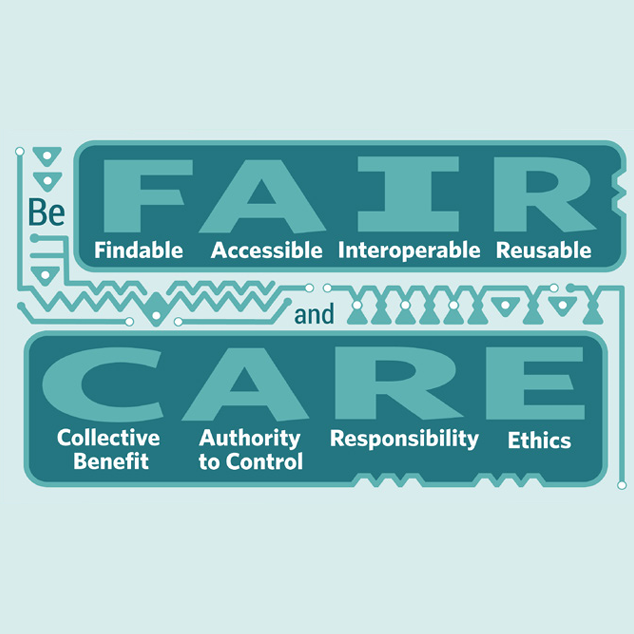

This short piece by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance briefly describes how the settler-devised “FAIR” (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) principles for digital data management don’t wholly meet the needs of Indigenous cultural preservation, and describes a complementary set of CARE (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, ethics) principles.

Reflect After Reading

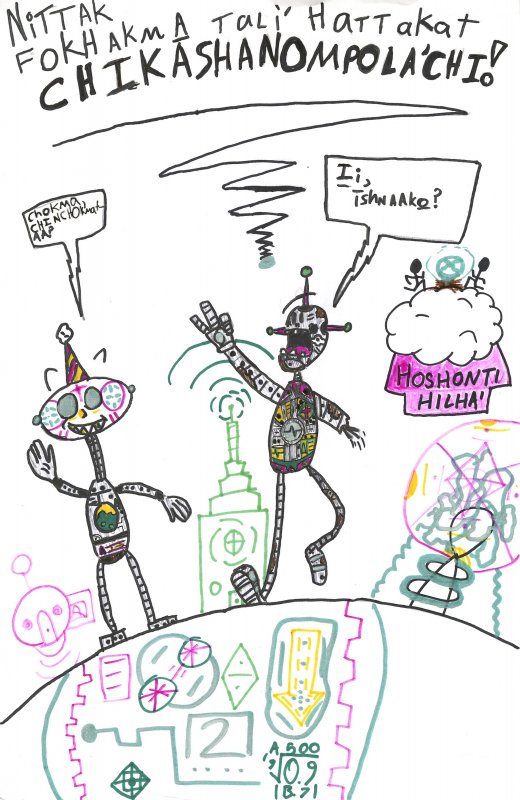

- The above image, drawn by a then-elementary-schooler, was published in the book Talking Indian by linguist Jenny L. Davis (enrolled member, Chickasaw Nation). Have you ever seen a science-fictional depiction of the future where Indigenous languages were centered? Have you ever seen a science-fictional depiction of the future where Indigenous languages were featured at all?

- If so, in what other ways was Indigenous cultural and personal presence in the future explored in that story?

- If not, what cultural norms contribute to you not having encountered this in your art and media experiences so far? What might this say about the kinds of futures a settler-centered culture allows itself to envision? How might the norms prevalent in fictional futures shape real-world ideas of the future and plans for the future?

- Tuck, McKenzie, and McCoy (2014), in the same article quoted above, wrote that “[a]ny form of justice or education that seeks to recuperate and not interrupt settler colonialism, to reform the settlement and incorporate Indigenous peoples into the multicultural settler colonial nation-state is invested in settler futurity” (p. 16).

This provocative statement asserts that even many social-justice-oriented educational reform goals – such as diverse curriculum including Indigenous voices alongside other diverse voices, or equitable funding of state schools – are still premised on settler futurity, e.g. the ongoing existence of a public school system run and funded by a settler state on Indigenous land.

Not all Indigenous scholars discuss Indigenous futurity the same way. For example, Myaamia scholar George Ironstrack (personal communication, March 19, 2024) has described the cultural revitalization work of the Myaamia people in terms of Indigenization rather than decolonization, emphasizing additive and reciprocal work centered on Indigenous cultural thriving and futurity. Likewise, the CARE principles described in the reading above aim to complement the FAIR principles, rather than displace them.- As you engage with the artworks below, note: How do these different artists envision Indigenous futurity – does their work envision an uncolonized future, and Indigenized future, an inclusive/diverse future, or some other vision of the future?

Exemplar Artists + Works

Explore these works by contemporary Indigenous artists/thinkers/makers who are engaging with concepts around Indigenous futurity.

As you explore, choose two works to research in greater depth which you may include as exemplars in your own lesson on envisioning the future. Consider: How do these artworks resist settler futurity? Do their visions of Indigenous futurity reflect decolonial, Indigenizing, or other strategies of envisioning Indigenous futures?

Elisa Harkins

(enrolled member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation)

Scott Benesiinaabandan (Anishinaabe, enrolled member of Obishkkokaang/Lac Seul First Nation)

Keara Lightning,

illustrations by Caeleigh Lightning

(Nipisihkopahk, member of Samson Cree Nation)

Susan Blight (Anishinaabe, Couchiching First Nation)

Cara Romero

(enrolled citizen, Chemehuevi Indian Tribe)

Cara Romero

(enrolled citizen, Chemehuevi Indian Tribe)

Cara Romero

(enrolled citizen, Chemehuevi Indian Tribe)

Naphtali Faulkner

(Ngai Te Rangi Māori)

Keara Lightning

(Nipisihkopahk, member of Samson Cree Nation)

Cannupa Hanska Luger

(enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold)

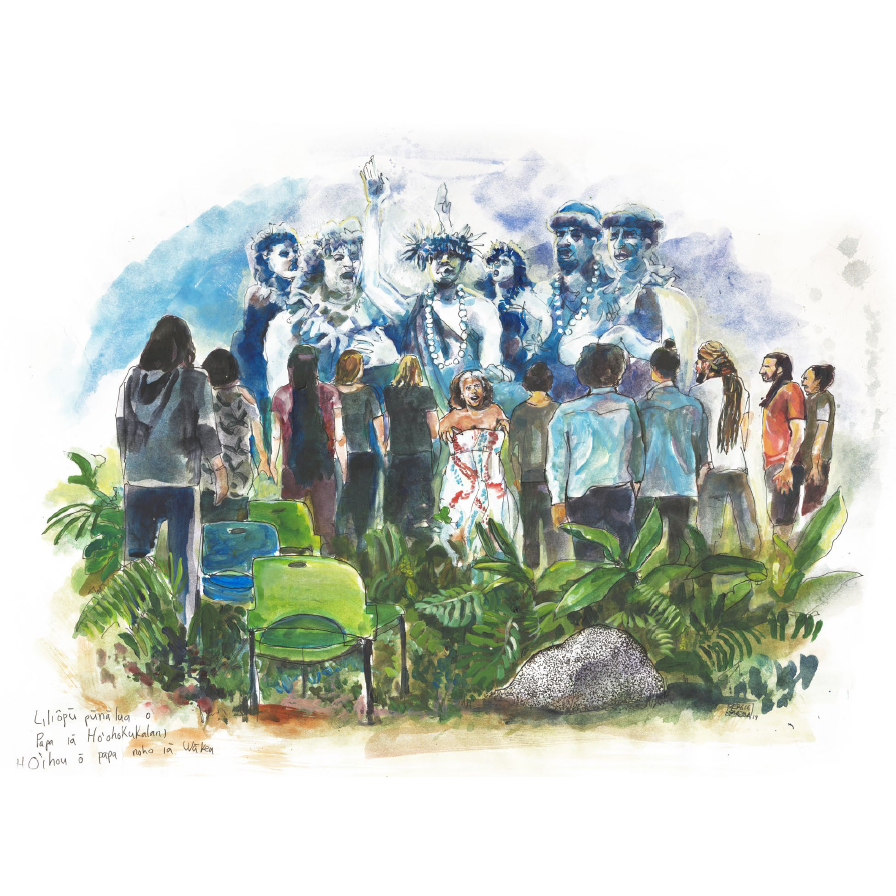

Daniel Kauwila Mahi

(ʻŌiwi Hawaiʻi) and the IIF Skins 5.0 Cohort

(Playable game download)

Danielle Boyer (Ojibwe, enrolled citizen of the Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians)

Danielle Boyer (Ojibwe, enrolled citizen of the Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians)

Lesson Development

Having explored the above concepts and materials, now it’s your turn to plan an arts learning experience.

- The targeted age range, materials, and art activities are yours to choose.

- You are required to meaningfully include at least two of the above artists (feel free to explore the site for more!)

- You are encouraged to develop a lesson that involves some sort of digital making, but a meaningful physical making experience rooted in ideas from these digital artists is also a viable approach!

- Please use this lesson plan template to structure your planning

Consider: How might students design digital mappings or places that resist, subvert, or operate outside of settler-colonial understandings of land and place?

- How does the positionality (settler or Indigenous) of the student artist impact their approach to this problem?

- How does the positionality of you as teacher (settler or Indigenous) impact your approach to teaching this concept?

This page last updated on April 23, 2024.